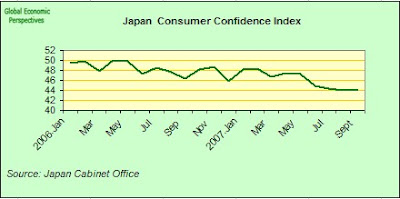

This continuing gloom among consumers suggests spending at home is unlikely to sustain Japanese growth should a global slowdown damp exports. Household confidence has been hit by sliding pay, a tax increase and the government's loss of pension records. Now families are also starting to feel the pinch from rising prices of food products like bread and instant noodles, even why technology services like mobile phone costs continue to fall, and the overall price index remains in negative deflationary territory.

All the components of the index - including employment - are well down on the levels registered at the end of 2006.

And you can now find this kind of quote - from Bloomberg - all over the place:

"The bad news about pensions and taxes is just adding up,'' said Martin Schulz, senior economist at Fujitsu Research Institute in Tokyo. Wages aren't rising even as companies' profits are increasing, ``so people are thinking: it's not going to get any better than this."

The worst part is that this assessment is probably realistic: it isn't going to get any better. This is how a rapidly ageing society works. The novelty is, perhaps, that this time it is finally sinking in.

You can also find a lot of this sort of commentary:

The country's largest companies expect the worst labor shortages in 15 years, according to the central bank's quarterly Tankan business survey. Bank of Japan Governor Toshihiko Fukui has said that the demand for workers will start to drive wages higher, supporting consumers.

This is the general hope, but it is a big white and empty one as far as I can see from the evidence, since it is the kinds of job which Japan is creating - given its ageing workforce - which is being reflected in those agregate wages, and nothing much is likely to change in this department anytime in the forseeable future.